Digging in, Part I: The History of Seattle's School Gardens

When we engage children in harvesting our gardens -- when we teach them about where their food comes from, how to prepare it, and how to grow it themselves -- they reap the benefits well into the future. (Michelle Obama, American Grown)

In recent years renewed interest in environmental education and child nutrition has led to an increase in the number of horticultural gardens at Seattle's elementary and secondary schools. Advocates of outdoor classrooms hail the conversion of asphalt jungles into green spaces. While this may seem like a relatively new phenomenon, in fact, gardening has been a part of school programming going back a century -- with peaks and valleys in interest along the way.

Early 20th Century: The School Garden Movement

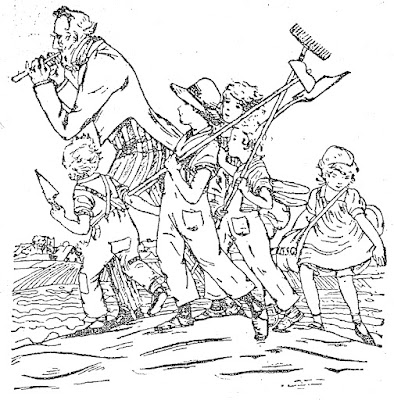

The early 20th century saw a surge of school gardens and related projects -- so many that the efforts became a "movement." The school garden movement coincided with the social goals of the Progressive Era, the City Beautiful movement, and educational theories that emphasized vocational training and home economics. Concern over rapid urbanization and nostalgia for country life gave impetus to the movement. In the words of the Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson (paraphrased by a reporter), boys involved in school gardens "give promise of living useful lives away from the storm centers of humanity." (SDT May 4, 1905)

The Seattle School District jumped into the cause in 1914 with an experimental program, offering cash subsidies for schools that wished to take on a garden project. Four schools took up the challenge: Emerson, Brighton, and Whitworth Elementary Schools in the Rainier Valley and West Woodland Elementary near Woodland Park. A report to the district board of directors the following spring included testimonials from personnel at the four schools enthusing about the project and providing insights into the workings thereof.

A Mr. Gray at Emerson School in the Rainier Beach neighborhood described how the garden instilled responsibility in the children:

The feeling among the older pupils that they have the privilege and responsibility of cultivating the "problem crops," leaving to the younger ones the raising of the common, easy kinds, adds interest and dignity, it would seem.

Mr. Gray also took it upon himself to teach the older boys rose pruning and propagation.

Principal B. Dimmitt of Brighton School in the Rainier Valley (now Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School) waxed eloquent about the benefits of the school garden, particularly as it encouraged home gardening:

I am of the opinion that more than half the families of the district have home gardens and much of this has resulted from the work carried on by the school. The children take much delight in the work at home and in reporting the same at school. From reports that incidentally reach my ears, I am inclined to think that the whole community is pretty well pleased.

Dimmitt goes on to add that he feels the garden work needs "constant definite direction," presumably from the higher-ups, and that "credit of some kind should be given to the pupils." Miss Hart at Whitworth School expanded on this theme:

The only thing needed to make school gardening delightful, instructive, profitable as a life interest and recreative as well, is for it to have a place in the course of study and be done during school hours, systematically planned and intelligently required as other school work is done.

It is fairly clear from the report and from subsequent news reports that the twin goals of the program were (1) to encourage children to take the skills they learned back to their homes and start gardens there, and (2) to provide vocational training, particularly to boys. In many cases children were encouraged to market and sell their produce.

From this point, school gardens proliferated throughout the city, with support from the school district, PTAs, garden clubs, and other, mostly women-led groups. Exhibits and contests promoted and rewarded the work of children tending school and home gardens. Where schools had no space for a garden, teachers sought out available space nearby -- a vacant lot or a corner of a church ground.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Orca School cookbook. Courtesy Rainier Valley Historical Society

Whitworth School - A Legacy of Gardening

I think if anybody wants a garden, this is a good time to start one. So when fall comes you will be able to enter the garden show. Anything will be accepted, from Forget-Me-Nots to squash. Who knows? You might even win a blue ribbon! (Lavina Stratis, age 14, Whitworth High Lights, June 1941)

In 1914, the Lakewood Civic Improvement Club awarded prizes to the children who grew the best vegetables and the best flowers in the Whitworth School garden. As noted above, Whitworth was one of four Seattle schools participating in a district experiment in school gardening. For reasons difficult to determine in hindsight, Whitworth was mentioned frequently in news accounts of school gardens for years to come.

Five years later, in 1919, Whitworth School was deemed to be "100% garden converted," meaning that every child from the fourth grade up was taking part in the garden program. The recognition came from the United States School Garden Commission; the local paper implied that Whitworth might be the only school in the country to achieve this goal.

Whitworth students participated proudly in the Victory Garden campaign during World War II. For several years the school held a "county fair" celebrating the work of students and their families. In 1942 11-year old Marilyn Ives won a blue ribbon for a "Victory Garden Parade" made of vegetables turned into dolls with painted faces and pipe-cleaner arms. Each doll carried a tiny garden tool. 12-year old twin girls won recognition for "a freak tomato raised in their joint garden," and "A tremendous red cabbage, grown by Jean Veldwyk, 11 years old, won a blue ribbon." (Seattle Daily Times, September 25, 1942)

Fast forward to 2007 and Whitworth inherited a garden program when the Orca School moved in. Orca, an alternative K-8 school with an emphasis on the environment and experiential learning, had established one of the first school gardens of the new era at its previous site at the old Columbia School in Columbia City in the early 1990s. More on that later on. Orca at Whitworth continues that tradition; within a year of the transition, the school had a new garden, combination greenhouse and science building, a garden educator on staff, and a renewed commitment to helping kids "learn about science while digging in the dirt." (Orca website)

______________________________________________________________________________________

War Gardens: "Furrows of Freedom!"

World War II saw the revival of garden patriotism in the form of Victory Gardens. Again, families were urged to support the war effort by growing their own produce. Schools followed suit, as did churches, military bases, Indian reservations, and even Japanese internment camps.

Comments

Post a Comment